1969

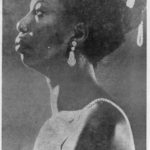

Caught In The Act: Nina Simone

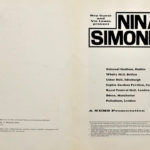

Ford Auditorium – Detroit, Michigan

by Bill McLarney

Nina Simone, more than most popular singers, is a dramatic artist. Her nuances of gesture and facial expression are as much a part of her art as voice and words. Those who heard her at Ford Auditorium could not experience her intensity as fully as audience who have the good fortune to catch her in a small club. Nor was communication served by the arrangement of the stage, which left the singer, when seated at the piano, with her back to part of the audience. One of the components of a Simone performance is that you overpowering gaze which picks you out of the crowd and says “You damn well better pay attention.” You do, and dig it. So much for minor complaints. So sure is Miss Simone’s grasp of audience psychology that she could probably communicate while handcuffed, gagged, and blindfolded.

The concert was an important occasion for Detroit’s Simone fans, who are far too used to hearing her as part of an overstuffed package with five or six groups allotted 20 minutes each to rush through their thing. This audience was ready, and they were Nina’s from the opening bars of “Times They Are A’Changin’,” which is introduced as “a 1969 hymn.” If the performance opened with a hymn, the whole concert was a sermon. And with “Times,” High Priestess Nina adhered to the first part of the time-honed formula for sermonizing: “First tell ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em.” Whatever else Nina Simone may tell ’em, there’s always this message. Times are changing.

You say you’re tired of being told “messages” in art. OK, I agree it’s been overdone. Much art can and should be viewed as abstract, with the emotional and ideological interpretation left largely up to the beholder. Not so with Nina Simone. Her music comes from a particular point of view, makes a comment, and offers an explicit program. To miss these things is not to have heard her.

The priestess ladles out fire and brimstone on Go To Hell. It’s almost frightening to observe the degree of control she exerts over he audience. Her emotional statements, while no less personal or sincere than those of other musical artists of her stature, are calculated to achieve a precise effect on the listener. You may think you’re too hip to succumb to such an approach, but Nina can mess up your mind. No matter what you want to feel or think, she has her way. She could be a demagogue, but not one to fear. For, as guitarist Schackman observed, “She’s never destructive–except when she needs to tear something down before she can build something better.”

A few bars ruminative of After Hours-style piano segue into a gospelish feel. Appreciative “yeahs” show that the audience is with the artist even during this slight musical interlude. Now Nina can stop preaching for a while and give the people a little of herself. “I Love My Baby,” with Nina’s breaks and Brown on tambourine, is still churchy, musically, but the lyric is a secular story. “Do What You Gotta” is less sanctified and even more Nina–above all she is a woman.

Enough. The brief glimpse of the tender side of Nina has heightened the empathy, if that be possible. Now back to this mean world with Muddy Waters’ “Rollin’ and Tumblin’.” Nina’s spoken introduction tells it like it is about Muddy and the Cream; about black blues singers and white rock groups. Her comments may seem harsh to some. After all, she didn’t acknowledge Bob Dylan’s authorship of her opening number. But her speech isn’t about Bob Dylan or Cream or Muddy Waters, of whom so many Cream fans have never heard. It’s about the repeated and scarcely acknowledged borrowing of black artists’ creations by white musicians; about the economic and social implications of this reality. Compared to the Claptons and the Bloomfields, BB King is still scuffling.

The tune offers a taste of jazz with a good brush solo by Brown and an Afro-style rhythmic exchange with Irvine and Schackman one tambourines and Perla on maracas. Nina, up now, dancing sinuously, contributes to the music with a device known as a libra-slap. There are those who put Miss Simone’s dancing as “entertainment,” whatever that may be. Some of those people do praise Monk’s onstage antics. If it’s hip for the High Priest to dance, why not for the High Priestess?

Back to the sermon now, with the piano-organ sound and the congregation clapping rhythmically. Nina wonders how it feels “To Be Free,” the closes the first set with the Beatles’ “Revolution.” Announcement of the title brings scattered applause. What kind of revolution are they applauding? The lyric makes it clear what kind Nina’s thinking about:

“When you talk about destruction, count me out.”

Nina finishes and stalks offstage. Suddenly the lights go out, the band sets up a throbbing roar, cymbals cash, and it’s over. Revolution indeed. A gimmick, yes, but a good set closer.

The second set opens with “Four Women,” Nina’s biggest hit in Detroit. If any rapport was lost during intermission, it’s immediately regained. Unlike many singers doing their hits, Nina gets better with repetition. In this case she has dropped the affected “pain…agane” pronunciation of the record and later her half-rhyme stand. (Poets must learn to read their own work.” And she is more fully into the characters. Her saucy portray of Sweet Thing draws a chuckle from the crowd. (Elizabeth van Der Mei, in Coda, wrote “Nina is Peaches, the mighty mistress of the biting rap line.” Okay, but don’t put her in a sack, Liz. Nina is Aunt Sarah, Safronia, Sweet Thing, Peaches, and a lot of other people when she chooses to be. She is not only of history, she contains it.)

Next, Peaches’ adversary, “Mister Backlash.” Nina has extended Langston Hughes’ original lyric. Two further glimpses of Nina Simone, poetess (both unrecorded to my knowledge) follow: the almost mystical “Suzanna” and “The Desperate Ones.”

Lyrics seem to be back in style, and a number of popular musicians are penning good ones. With all due respect to the Campbells, Gentrys, and McCartneys, isn’t Nina Simone due some recognition in this field? (Also her husband, Andy Stroud, who is her collaborator.)

“Ain’t got no money. Ain’t got no clothes. Ain’t got no…”

A long recitation. Sounds like the blues (in a mood). But wait. What has Nina got? Like Walt Whitman “of physiology from top to toe” she sings:

“I got my hair. I got my head. I got my…”

And in partial answer to an earlier question:

“I got my freedom down in my heart. I got life.”

The sermon is complete. Surely the audience gets the point. The fight for freedom begins with the self.

For the closer, Nina announces “I’m going to have to leave you sad.”

Everyone knows it, but one number of the congregation shouts it: “It be’s that way some time.”

“But next time I’ll leave you glad,” she adds.

And so into “The King of Love.” Martin, of course. Sad, yes, but beautiful–and pertinent.

If little has been said of the sidemen, that is to be construed as high praise. Their role is, as organist Irvine puts it, “subliminal.” If they should goof, they would be noticed. Nina guards against that chance by always hiring good musicians and by maintaining one of the most rigorous schedules in the business. That way she can be sure her sermon gets across.

W. Somerset Maugham wrote of the artist: “His sermon is most efficacious if he has no notion that he is preaching one.” In general I agree. But now and then I don’t mind a premeditated sermon. Not when the artist knows the sermon as well and believes it as fully as Nina Simone.

Nina Simone Delivers A Message

By Bob Micklin

If you’ve ever watched Nina Simone sing, you know what the word charisma means. She has an ability to communicate with, to inspire a response in an audience that is shared by only a handful of other performers. “So sure,” a Downbeat magazine reviewer wrote, “is Miss Simone’s grasp of audience psychology that she could probably communicate while handcuffed, gagged, and blindfolded.” Probably true, and that control is not at all accidental.

She is, first of all, a striking-looking woman who uses her naturally intense, regal manner to overpower her audiences with stage presence. Then there is her voice, a unique vocal instrument that can lash like a whip or smooth like a lullaby. It is not a “pleasant” voice, just a Nina Simone is not a “pleasant” singer. But it is just the right voice for her highly dramatic, often evangelical singing style.

On a recent afternoon, Miss Simone sat in the Manhattan offices of her husband, Andy Stroud, who is also her personal and business manager, and discussed her powerful way with an audience. “Oh, I for on that, I work on that,” she laughed. “I plan each show around the audience. I try to plan a concert. About an hour before I go out on stage. I watch the people. I listen to them. Then I try to relate my songs to a particular mood I’m trying to develop.”

In recent years, those songs have increasingly been songs of protest — especially racial protest. In them, she sings not of hate but of justice (“Go To Hell”), of freedom (“To Be Free”), and of pain (“The King of Love”). Rather than alienate a possible segment of her audiences, she feels her protest work has increased her stature as an artist.

‘My People Need Me’

“If I lose fans because of racial songs, well that’s too bad,” she said. “I won’t stop what I’m doing. My feelings come out of me as a black woman. My people need me. You know. I do a lot of college concerts, and I don’t think I’ve ever had anyone walk out on me in places like Georgia or Louisiana. But in New York, I’v had people get up and leave. That’s funny, isn’t it?”

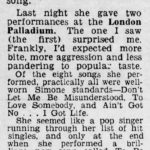

College audiences are her favorites. “They’re wonderful,” she said. “They’re so fresh and enthusiastic, and they’re willing to hear you out before they form any opinions about you. I don’t like nightclubs, and I seldom work them. Also, from a business standpoint, they’re not as profitable. I love the Village Gate (where she winds up a four-weekend stand tonight and tomorrow night) because it’s like home to me. That’s where I got my start in New York.”

She gets, she said, a different feeling from black audiences than from white ones. “I’m just more at home with black audiences,” she said, “they’re my people. If they feel moved, they’ll get up and dance or answer me back. The colored kids don’t seem as inhibited as the white kids. They’re used to carrying on and grooving if the music moves them. But it has happened a few times in Europe, especially in London.”

“You know, I don’t just sing about racial protest,” she said. “I try to do all kinds of material. I’ve always loved pop music. I sings songs by Dylan, the Beatles, Gershwin. I do ‘Don’t Smoke In Bed,’ which is an old one that Peggy Lee used to sing, and ‘I Don’t Want Him, You Can Have Him,’ from an old musical called ‘Red, Hot, and Blue.’ I love jazz, and melody. And when I want to relax, I listen to classical music.”

There was a time when Nina Simone dreamed of being a classical pianist. Born in 1933 in North Carolina, she never thought of herself as a singer. “We had a little quartet at home,” she said, “and there was always a piano in the house. We’d sing spirituals, and my whole family played the piano. We were very poor and we had no record player, but I took piano lessons. I loved the boogie-woogie piano style and I played a lot of that.”

At 18, she came to New York and studied piano for more than a year at the Juilliard School of Music. “But the money ran out,” she said, “and I started teaching piano in Philadelphia.” While there, she also studied music at the Curtis Institute. In 1953, she took a summer job in an Atlantic City night spot. “I was hired to play piano,” she said with a ironic smile, “but after the first night, the boss told me I’d have to sing too, or I’d lose the job.”

She changed her act the next night, singing virtually any song she could remember. She also changed her name to Nina Simone (“My mother was opposed to me being in show business,” she says, “so let’s leave it at that”), taking the Nina from a boyfriend’s pet name for her and the Simone from “I don’t know where.”

Since the mid-1950s, she has been recognized as one of the most affecting and original performers in the music business, and the depth of her experience in music has given her an assurance that only top-flight artists can understand. Her opinions, for example, of other performers may surprise those who think of her as being protest-oriented.

“My favorite singer?” she said. “Frank Sinatra. He can do no wrong. He’s part of my youth. I grew up with him. Oh, I think James Brown is very good too, but Sinatra. He’s in touch with the universe. You know, I never even heard (the late) Billie Holiday until 1953. She’s my favorite female singer. But there are two other singers who are just wonderful. Betty Carter and Anita O’Day. It’s a shame you don’t hear from them anymore.”

Black Blues vs. White

What, she was asked, did she think of all the white rock singers who have adopted the vocal inflections and delivery of black rhythm and blues singers? “I haven’t ever heard any white singers who have the strength and feeling of black performers,” she said. “In a way, I admire them for what they’re trying to do…to get a certain truth, but it just sounds wrong.”

“In defense of the white kids, though, you know that years ago black performers did the same thing in reverse. It wasn’t so popular to be black then. But the inflections and nuances of the blues have nothing to do with the notes. The black masses have always been trying to survive oppression, and misery, and the blues expressions have come out of those feelings. You have to have experienced those feelings. You can’t like,, or fake it. Like if some cat holds up a gun to you, you can tell by his eyes whether he’s going to pull the trigger. There’s no faking about it. This girl Janis Joplin (the white rock singer), for instance. I sure hope she doesn’t kill herself trying to do all those black things with her voice.”

“A lot of white kids do it because the music they’re singing — the blues — just sounds better sung that way. But you know, it’s not just the white kids who are in trouble. I’ve seen colored kids who can’t sing or dance worth a damn.” Nina Simone laughed. “We have the same broad spectrum in our race as you do in yours,” she said.

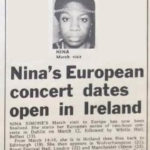

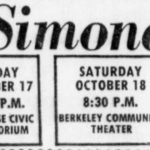

NET Festival ‘Sound of Soul’ television broadcast in the US, recorded during Nina’s 1968 European tour.

Parts of this were later released on Jazz Icons DVD.

click each to enlarge

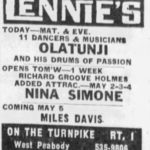

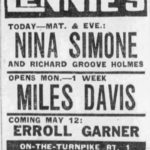

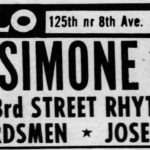

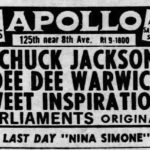

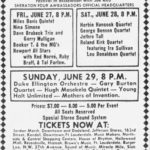

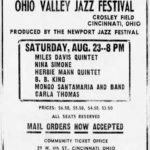

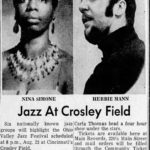

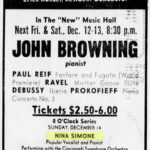

Hartford Courant:

Raleigh News & Observer:

Chico Enterprise-Record:

Charlotte News:

North Adams Transcript:

Troy Times Record:

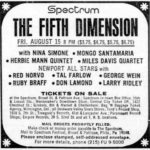

Tampa Bay Times:

Chicago Tribune:

Burlington Free Press:

Philadelphia Inquirer:

click each to enlarge

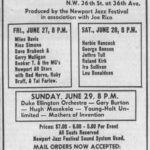

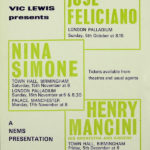

Elseviers Weekblad (from the Roger Nupie Archives):

Vancouver Province:

Hackensack Record:

London Evening Standard:

Rochester Democrat & Chronicle:

(All articles below provided by the Roger Nupie Archives.)

International Herald Tribune:

De Telegraaf :

De Volkskrant:

Het Vrije Volk:

Abendzeitung:

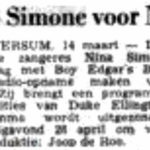

Netherlands – 3/17/69:

Le Figaro:

click each to enlarge

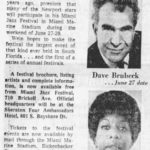

While in the Netherlands, Nina was scheduled to appear in Hilversum on the television program Avro directed by Theo Ordeman (for broadcast on 4/8), but she cut the performance short and it was initially reported that not enough footage was recorded for an entire broadcast (De Telegraaf – from the Roger Nupie Archives):

Another article provided by Sylvie states that the planned 4/8/69 broadcast of the footage filmed on 3/18/69 (but filmed in Bussum) was still going forward:

…so at this time it is unclear if Nina did record an entire show, where the recording took place, and if the recording was broadcast on television. This will be updated in the future should the correct/clarifying information be obtained.

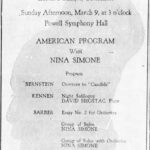

Footage of Nina’s performance and behind-the-scenes interviews were included on the DVD Great Performances: College Concerts and Interviews. Some footage was also included in a broadcast on Black Journal which aired in October of 1969.

click each to enlarge

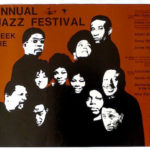

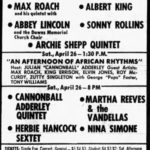

The first Pan-African Cultural Festival took place in Algiers in July 1969, seven years after Algeria’s independence. The Pan-African gathering was a genuine meeting of African cultures, united in their denunciations of colonialism and fights for freedom.

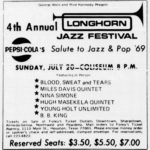

Nina performed alongside Miriam Makeba, Archie Shepp, Marion Williams, and others.

click each to enlarge

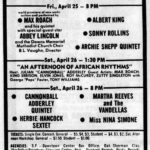

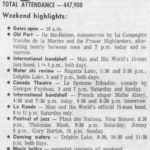

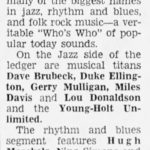

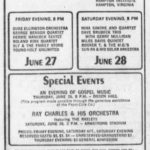

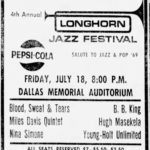

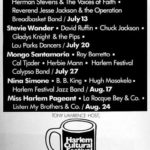

The Harlem Cultural Festival (also known as Black Woodstock) was a series of music concerts held in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park (now named Marcus Garvey Park) during the summer of 1969 to celebrate African American music and culture and to promote the continued politics of Black pride.

In 2005, a portion of Nina’s performance was released on the DVD disc in the DualDisc Soul of Nina Simone:

In 2021, parts of Nina’s performance were also included Questlove’s documentary for Hulu, Summer of Soul:

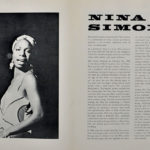

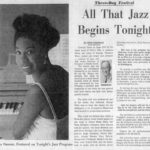

Nina Simone: High Priestess of Soul

by Phyl Garland

To her fans, she often seems a wily sorceress, disarming them of their common human defenses and luring them into forbidden portions of the self where the pain and raw ecstasy of intense emotion must be confronted without recourse to subterfuge.

She casts her spell with the fluid but frequently complex patterns of notes she etches on her piano and with the distinctive sound of her richly reedy voice. This voice of hers is not the finely honed tool of a trained singer, but it possesses something those other voices lack – an earthy naturalness, the compelling coarseness of a homemade instrument that might have been whittled by hand in the fields and then played with consummate artistry.

Yet the secret to her special brand of black magic lies beyond her sound in the message that always lurks somewhere in the lyrics of her songs and the way in which they are projected. For she speaks not only of love, but of the black man’s pain and passion whipped to a swelling rage, filling the sung phrases with her own spirit of rebellion. Always, when she does it, she is so for real and comes on so strong that she can make the unready squirm in the heat of the truth.

For Nina Simone, the “high priestess of soul,” music is not only an art, but an expression of life in all its verities. More than any other performer of the day, she has captured the essence of the black revolution and sings of it without biting her tongue. However, her stature as a versatile musician is considerable regardless of what she happens to be singing about, for this sorceress of song is an outstanding eclectic, a sort of one-woman summation of musical confluence. Though soul is the convenient label under which she is currently classified, there can be detected in her singing, playing and original compositions, the mark of all the major streams that have gone into the making of modern music.

There is the heavy flavor of black gospel music traceable to her beginnings as a little girl, then called Eunice Waymon, who was born in the almost infinitesimally small town of Tryon, NC, to a minister-mother and her handyman mate who shared a deep religiosity. It was in her hometown that her earliest fans, the townspeople, banded together and set up a fund in order to provide this musically gifted child with the classical training that lingers in the style of the mature artist she has become. Her pianism is laced with the techniques she learned as a student at Juilliard in New York and the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. But the touches of Bachian counterpoint have been mingled with the improvisational approach of jazz and the modulations of the blues.

As a singer, she is a distinctive stylist who plays with and around the melody, manipulating the words to create a tone-portrait of dramatic intensity. She “sings” with her whole body, with her facial expressions, alternately wooing and chastising the audience with her words. And when her exaltation can no longer be contained, she jumps up from the piano and moves rhythmically about the stage in a nameless dance of joy. There is only one Nina and that one is truly something else.

The public-at-large first became aware of Nina Simone back in 1959 when her sensitive rendition of Gershwin’s I Loves You Porgy established her as a star and led professionals to compare her to the late Billie Holiday, a peerless stylist. During those days and even into the early sixties, so much emphasis was placed on her position as a supper club songstress for the elite that it came as somewhat of a shock to the black public when she reentered their sphere of consciousness as a purveyor of protest songs. This was in the late 1963 when her composition Mississippi Goddamn was widely broadcast with its beep-beep deletions of a so-called offensive word. It was more than enough to convince blacks that she was a true “soul sister” who had been with them all along. Otherwise, she never could have written a song of such bitter fury.

Mississippi Goddamn, which marks a milestone in modern protest music, was written by Nina just after four little girls were killed in the bombing of a church in Birmingham, Alabama. This was the same year in which Medgar Evers, 37-year-old field secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi, was shot to death in front of his home in the capital city of Jackson. So it was that she wrote those memorable lyrics, accentuated by a furiously galloping piano:

“Alabama’s got me so upset;

Tennessee made me lose my rest;

And everybody knows about Mississippi-Goddamn!”

Thus she became established as the singer of the black protest movement, for she had given voice to the stifled rage of her compatriots of the skin. This reputation was consolidated in 1966 when she wrote and recorded a song entitled Four Women, based on the varying life styles and attitudes of four black women as linked to their skin colorings. It, indeed, struck a note of response in black women who heard it, for never had anyone expressed so eloquently and so openly that which had been their burden for centuries: a rejection of their own blackness, reinforced by the “fair-skinned, blue-eyed blonde” standards of the larger society.

Nina Simone who, herself, has abandoned the straight-haired image of her supper club days to wear a natural hairstyle, had it all there in her song Four Women – and a lot more, too. There is the black, wooly-headed “Aunt Sarah” of the first verse whose monumental strength has been drained into the unrelenting struggle to endure pain; the “high yellow,” straight-haired “Safronia” of the second verse who is the racially mongrelized product of a right white man’s forcible seduction of a black woman, which was the case throughout the dark night of slavery and the continually troubled dawn that has followed; the pretty, tan-hued “Sweet Thing” of the third verse who has sought a fleeting self-acceptance in the transient encounters of prostitution while using her inviting body to buy survival. Then there is the unruly, loud-talking, independent “Peaches” of the final verse, who comes closest to where so many black women of today stand, regardless of age:

“My skin is brown, my manner is tough

I’ll kill the first mother I see

My life has been rough

I’m awfully bitter these days because my parents were slaves

What do they call me? My name is Peaches.”

But she did not stop there. She has consistently included protest songs, hers and others, in her recordings and performances. One more recent number is I Wish That I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free, composed by the jazz pianist and lecturer Billy Taylor, with its resounding final lines:

“Say it clear, say it loud,

I am black and I am proud!”

But all of this might have been expected, for Nina Simone continually has reflected in her music the prevailing mood of black people, from the years of the 50s when she tried to track down an only reluctantly forthcoming acceptance by whites on their own standards and into the 60s when her utterance has been one of protest. And it must be noted that one of her latest records is entitled Revolution.

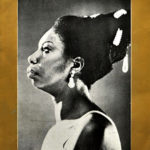

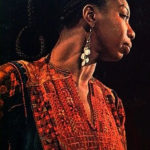

She is a slender, dark brown-skinned woman who carries herself with an ever-present, self-protective chip on her shoulder, as though telling the world, through her very stance, that it had better not mess with her. This shield of what might be called hostility is not directed exclusively at whites, for members of the working black press have sometimes pegged her as a difficult number. Yet others have lauded her for being “so nice and so cooperative.” Much of it might depend on the way in which she is approached and the mood she happens to be in at the time. She is at her best though, when met at the midtown Manhattan offices of Stroud Productions, the management and booking firm presided over by Andrew Stroud, a former police detective who has been her husband of nearly eight years. There all appointments for interviews are carefully checked, confirmed and reconfirmed by a secretary with a crisp, “white-sounding” voice, though she turns out to be black. Andy Stroud, a stocky, good-looking fortyish man with an easy-going manner and outgoing personality, takes a personal interest in setting up his wife’s appointments and speaks of his desire to build the firm’s production activities to the point where Nina Simone, its mainstay at the present, will be able to take long vacations and devote more of her time to composition and doing just what she feels like doing, particularly taking care of their six-year-old daughter, Lisa Celeste.

It is early afternoon of a brisk mid-winter day when Miss Simone arrives after a drive into the city from her suburban Mount Vernon home. She is wearing a fitted lightweight tweed maxi-coat that sweeps nearly to the floor. Beneath it is an above-the-knee-but-not-quite-mini-dress of semi-mod design, set off by beads, a bit of jewelry and the headband clasping her natural above her brow. From the moment she enters, there can be no question as to whether or not she is the star, but her manner is not overbearing. Guarded, might be the term one might use for it, and it is easy to overlook when one considers all the rebuffs and frustrations she must have encountered as a black girl from the South who had nerve enough to come North to the roughest city in the world, armed with nothing but a formidable talent and a whole lot of guys and, above all, to really make it.

“Now what is this for?” she demands brusquely with an unsmiling glance at the prospective interviewer, triggering with this affected iciness the first twinges of uncertainty.

The first timidly proffered questions, interspersed with a few nervous smiles intended to reaffirm good intentions, draw blunt “yes” and “no” answers leading to nowhere. But gradually the wall of ice begins to thaw and she comes to speak from out of her true self. There are even several broad smiles, so unexpected as to be dazzling and a spontaneous laughter that is almost musical. Then one realizes that she is no ogre, no pillar of glacial arrogance, but an artist who might have good reason to distrust those who prey upon celebrities. Similarly, she seems to understand that this is no voracious beast seated before her but simply a lover of music who greatly admires those who are masters of it. She is questioned about her use of protest material as compared to the more conventional songs of her earlier career. Has this switch been a deliberate one?

She answers:

“I suppose one might say that because, for the first six or seven years of my career, I mostly played night clubs and supper clubs. But during all those years, I had a quite a vast repertoire. So when I was in supper clubs and night clubs, I simply played the things that were applicable to those places. That was for about six or seven of the 15 years I’ve been in show business – since 1953. But now that my people decided that we’re going to take over the world (a knowingly affectionate and not at all condescending laugh), I’m going to have to do my part.”

From there on, the interview falls into a compatible groove, with G. being the author and S being Miss Simone.

G: You know, it seems to me that what you do in music is like preaching. You’re telling the truth and spreading the word, the way Baldwin has done it in writing, but you’re using music to do it.

S: That’s right. Um-hummmmm. I was told by H Rap Brown once – and I was highly complimented – that I was the singer of the black revolution because there is no other singer who sings real protest songs about the race situation that I know of. Oh, of course, a lot of guys are doing it now that it’s become a popular thing, but I mean to really mean it and to try to give inspiration to my people – I think I’m the only one. I like it! I like the idea.

G: I think you really began to get through to all of us when you did Mississippi Goddamn! So many of us felt the same way.

S: Yes, I can understand that, but I’d like to clear up one thing. I hope the day comes when I’ll be able to sing more love songs, when the need is not quite so urgent to sing protest songs. But, for now, I don’t mind.

G: Because of the sort of material you use, it seems that you might be the sort of person who believes that the artist should reflect the time in which he or she lives.

S: It has to be that way, my friend. I live that. There’s no other purpose, as far as I’m concerned, for us except to reflect the times, the situations around us and the things that we’re able to say through our art, the things that millions of people can’t say. I think that’s the function of an artist and, of course, those of us who are lucky leave a legacy so that when we’re dead, we also live on. That’s people like Billie Holiday and I hope that I will be that lucky, but meanwhile, the function, so far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times, whatever that might be.

G: I guess that means the unfortunate state in which so many things are today, racially and otherwise, I mean.

S: Yes, but in many ways, it’s a good time to be alive. I feel more alive that I ever have and this is true for many of the black people. Let’s face it. It’s a struggle and a big fight, but I would rather be fighting for something that I know is going to make a better person out of me and to make me feel like I’m alive, more that to be like we used to be – just accepting and going along.

G: I remember seeing you perform in Chicago shortly after the assassination of Dr. King and you seemed to project an image of defiance and courage. I believe that you let your true feelings come through that night, but, at the same time, your range of materials is so great that you seem to be expressing, simultaneously, the universality of human feelings. Is this also what you attempt to do through your music?

S: Yes I am. Music is one of the great forces in the world and ever since I can remember, I’ve loved music and I’ve been interested in all kinds of music. From the beginning, I’ve been singing all kinds of music and I want to continue to do that. Of course, again, the most important thing these days is to make certain that I make some statement on the stage about how we feel as a race. That’s more important than anything. But I love all music from all lands.

G: I think I’ve read somewhere that your training in classical music was your earliest major influence.

S: Let me clear that whole thing up. When I was three years old, I played by ear, I traveled with my mother who gave revivals, so I was playing gospel and jazz and blues for about five years before I started to play classical music. I started studying music when I was eight, but before then, I was playing what was real swinging. I mean like what they have in Holy Roller churches. So I want to clear that up because some people think that first studied classical music and switched to jazz. I played for revivals and I was colored long before that!

G: I can detect gospel influence in your music in general and particularly in numbers like Take Me To The Water.

S: Yes (with an exceptionally broad smile), you know where that comes from! My Mama had us all baptized, way way before. Some of my most fantastic experiences – experiences that really shake me, not that I think of them – happened in church when we’d have these revival meetings. I’d be playiNnNnNnNnNng, boy! I’d really be playing. I loved it! Folks would be shoutin’ all over the place. Now that’s my background!

G: I can feel that in your music. Would you say that this gospel background supplied one of the key elements into your musical style?

S: Yes! (She breaks into a rhythmic chant of words repeated for effect of the sort black ministers employ while delivering their sermons.) That’s the power! That’s the power! That’s the power! And I’m grateful…I’m grateful.

G: It seems to me this fire, this intensity to be found in gospel music has been carried over, into the area they now call soul music.

S: Right!

G: It even sounds very much the same.

S: It is the same. (A shared burst of hearty laughter at mutual recognition of a black phenomenon.) It is the same, I mean really! (The last word, commonly used by blacks for emphasis, is always shot out quickly with a heavy accent on the first syllable.) The more you listen now to the radio – there are about five or six groups I can point out that came straight out of the church, I mean really, I mean the feeling. It’s the same! But they just call it soul music. (Another laugh.) It bridges that gap. You know my people…my parents have a way of looking at it – I always give them a hard time about it because I have never believed in the separation of gospel music and the blues. Gospel music and the blues have always been the same. It’s just that Mama and them were so religious that they wouldn’t allow you to play boogie-woogie in the house, but would allow you to use the same boogie-woogie beat to play a gospel tune. (She cracks up behind this.) I just don’t agree with it because our music crosses all those lines. Negro music has always crossed all those lines and I’m kind of glad of it. Now they’re just calling it soul music.

G: But this music is the way that we have expressed ourselves ever since we’ve been here.

S: Really!

G: And I’m happy to see people taking pride in it instead of pushing it into the background.

S: Oh, it is time. It’s after time. Oh-Lord!

G: Getting back to your own music, I’ve read somewhere that in your early years you listened to the late Billie Holiday and were influenced by her style.

S: That’s not exactly right, because I knew who she was, but I never heard her sing at all until 1953 when I came to New York. I was just a country girl (a light chuckle), you have to understand. I came from North Carolina and them music I knew was the gospel music and the blues music that we did in church. Mama didn’t even allow me on the other side of town where “the sinners was.” (A bigger chuckle.) And there was the classical music. But when I came North in 1953, I met someone who introduced me to most of Billie Holiday’s records, at which time I fell so in love with her that I learned Porgy, which was my first hit. So I didn’t do any studying of her when I was small. I didn’t even know the woman, but I think I was just about in my late teens when I heard her.

G: One thing that has impressed me is how so much of our music forms a continuous stream, moving from one generation to the next without losing its basic characteristics.

S: Isn’t it wonderful? Some of the same songs, the same source. And I’m so glad. (She breaks into another chant.) Oh I’m so glad! Oh, I’m so glad we haven’t changed things. We can’t help it though. (A knowing laugh.) My mother told me when I was a kid, she said, ‘I gave all my children back to God,’ she said, and what she meant was that there is a thing inside of us. We’ve had it since before…our forefathers, our ancestors from Africa. There’s a thing that we have that makes the essence of us and I don’t think it has anything to do with a choice. We’re just the way we are, as a people. Who invents slang?

G: Everybody’s saying “MAAaan’ now.

S: We came up with that. (Mutual smiles.)

G: And what about the use of words in speech to lend to a certain rhythm to a sentence?

S: RHYthm! (She sings out the word.) It’s the truth, really! It goes all the way though us.

G: And the way we move?

S: It’s the truth! Rhythm!

G: And I don’t need any anthropologist to tell me these things. I just call it black soul.

S: Really. Yes it is!

G: But what is your opinion of some of the new music being created by young white artists?

S: You mean rock?

G: Yes.

S: Well, I’ll tell you. Some of these white kids are trying very, very hard to imitate colored people and they’re doing it very well. Some of them actually have got some real fire and I don’t know what price they’re paying for it, in the sense that I don’t know how much drugs they have to take; I don’t know how far out they have to go in their heads, but some of the music that comes out of some of these rock groups has got some real fire. It’s like, they’re trying to hard to get that soul that I think some of them have got a hold of it, yes I do. Like I said, I don’t know what price the they’re paying, because of the kids I know about who really sing good hard rock, which is the equivalent, as far as I’m concerned, of Holy Roller revival music, most of them are hooked on drugs and I mean really out there, and that’s a big price to pay to sound colored. Most of it is junk, but a lot of them are good and there’s one guy I’d like to speak of who’s not like us at all and doesn’t try to sound colored. But he has his own thing, and I respect him and I really admire him and that’s Bob Dylan. The man is his own man, has his own statement to make and makes it. He’s a universal poet. He’s not trying to be white or colored. The man is just a great poet. And I admire him very much.

G: I certainly agree with that and do respect all who are developing their own things, but what about these young white soloists and groups who seem to pop up overnight and, before you know it, they are on the Ed Sullivan Show or some other television show, doing a song originated by a black artist or group that has never even been on television.

S: Oh, I resent that! I deeply resent that. It makes me very bitter and very mad and it has for years, but I like to think that, you know, our music is leading the parade now, all over the world, so it really doesn’t mean too much, as far as I’m concerned. I mean, I still resent it, but I think it’s just a matter of time before we take over television too, I mean just take it all over, I really do.

G: But meanwhile what can be done to help some of the young black groups and artists get wider exposure?

S: We have to work on that. I don’t know how because I know that, say a little group will get up a hit tune and then some white group comes along and takes the dress, the songs, the style and next thing you know they’re featured on television. Now, we have to put an end to that. I don’t know hooooow. This might sound contradictory to what I said before about us not having to worry about them, because we do have to worry about them, because if you get a hundred white groups like that and they get exposure, they have actually gotten the advantages that a hundred black groups could have gotten who created the music. I don’t know how to put an end to that, but the young black kids have got to get the advantages. They’ve got to stop the white ones from stealing our stuff, getting the money and then influencing a thousand other white kids to think these were their ideas. That’s also what they do. They sing songs and then white kids who don’t know any better think they did them. I know we’re slowly moving along , but I know that with all this fighting and going on, especially in the colleges, I think the young kids’ll get it all together.

G: Do you think that this spirit of rebellion and demand for change to be found among young people of both races might lead them to alter white attitudes in general and to influence the establishment for the better?

S: I have no idea, because, I’m going to tell you the truth. I distrust the establishment so much and so deeply that I don’t even think in terms of their giving us our rights. I don’t even THINK about that. All I think about is this, and this is the essence of me, what I want for the rest of my life. I ready it in a book, and I don’t recall which one, some black book. It’s a four line poem and it said: “Brothers, brothers everywhere…and not a one for sale.” And I think that says the whole thing.

G: Amen!

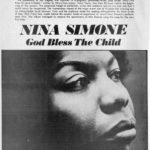

Nina Simone: God Bless The Child

by Jim Delehant

Nina Simone was born Eunice Waymon in Tryon, North Carolina, the sixth of eight children. Her mother worked as a housekeeper and her father was a handyman by day. At night and on Sundays, he wore the robes of an ordained Methodist minister.

Many years later, the name and talent that is Nina Simone sold out the famed Westbury Music Fair, the year-round theater-in-the-round at Westbury, Long Island, long before the scheduled concert date. Two nights before the show, however, one of 1968’s unbelievable series of tragic events occurred: the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

The immediacy of the tragedy was captured in a poignant, sometimes bitter, song called ‘Why? (The King Of Love Is Dead)’, written by Nina’s bass player, Gene Taylor, less than 24 hours before the beginning of the concert. The emotional height of performer, writer and audience was so true and real that it could never be recaptured. The tremendous impact of the tragic event was at its peak that evening and an indescribable bond between Nina and the audience made this reading unforgettable. By sheer stroke of fate, RCA Victor had, weeks before the concert, made arrangements to record Nina Simone’s performance live. This album managed to capture the spontaneity as Miss Simone sang this song for the very first time.

HP: Do you feel close to Ray Charles?

Nina: Not any more than I do to ten or twelve others. Why do you ask?

HP: Something in your passionate involvement with songs. Who do you feel close to in the male category?

Nina: The way you put it, I’d say Ray Charles. I never thought of that. But thank you, that’s a compliment. I do love to sing Jacques Brel songs, intensely. I get terribly excited, just by reading a couple of lines in any one of his songs.

HP: Are you from a gospel background?

Nina: The same old thing. I was reared in the church from the age of three. I’ve played piano since I was three. I performed at revivals and for my people around North Carolina for several years. People around town collected money to send me to school. By the time I was eight I was taking classical piano lessons and I wanted to be a concert pianist. But that didn’t work out. I graduated from high school and my formal education ended.

HP: You have a very cultured manner of speaking.

Nina: Well, that depends on the time of day (laughter) understand? I’ve toured a lot and been to Europe. It depends how I feel. My name sounds French but that’s just a stage name. I live in Mt Vernon, New York now.

HP: Did you ever have vocal training?

Nina: Not really. I used to accompany students in a popular vocal studio in Philadelphia and that influenced me. At the time, nightclub techniques rubbed off on me. But never formal training. My singing, if you want to call it that is merely another medium of expression. Just an instrument I play. That’s how I see my voice.

HP: To me one of your most moving performances is ‘Don’t Smoke In Bed’.

Nina: Oh thank you. I heard that a long time ago in a movie. Maybe thirty years ago. It’s one of many pop songs that stuck with me as I grew up. When I choose material for an album all these songs I grew up with pour into my head.

HP: Are you aware of your highly unique style?

Nina: Yes, I am. I know I’m different, but I don’t think about it. You can’t be different if you look at it. Being gifted is different. I had that in my piano playing. I’m very thankful for that. I’m very aware of that. The style and what I fed is just me. I never worked at it. It just happened.

HP: Do you feel a lot of female singers still try to sound like Billie Holiday?

Nina: Yes. But less and less now. Many of them turned up when Billie died. I have many warm thoughts for her ideas. You couldn’t find a better influence than Billie. God, she was something else. I got ‘Porgy’ from her which I did in 1958. Billie happened to hear a tape I did of it long before it started selling and she wrote me a note saying she liked it and hoped I would be successful. That autograph is very precious to me

HP: Can you remember particular songs that knocked you out as a child?

Nina: Oh yes, an old hymn called ‘God Be With You Till We Meet Again’. I remember it vividly, because it’s the first song I picked out on piano at the age of three.

HP: When did you move from gospel to pop?

Nina: After my classical training when I was twenty-one. That’s when I started going to nightclubs and hearing all kinds of music. I had heard blues and jazz all my life but I was never aware that it was associated with nightclubs and drinking. We didn’t have a record player, but we had a radio and a piano and somebody in my family was always singing or playing or dancing. Oh, I heard a lot of boogie woogie too. That killed me, because I loved to dance. I had to play that when mama was out of the house because she didn’t allow it. Somebody would watch out the window to see if mama was coming.

HP: What made you come to New York?

Nina: Right after high school I came to a summer course in piano at the Juilliard School of Music.

HP: Did your parents want you to be a classical pianist?

Nina: When a child is gifted, people try to help that child. I had been playing by ear and when I was seven a white woman heard me playing in a theatre and went to my mother with an offer to give me piano lessons. That’s a very high goal to have, study eight hours a day to be a concert pianist. I didn’t even think about it. I just got into it. I was very young. As I got older though I wanted a life of my own. The classical training was very demanding and thorough. It was a very sheltered existence. Even though I heard blues and gospel on the radio sometimes, it was always back to the piano and study and give recitals.

HP: So you have a good technical knowledge of music?

Nina: Yes. I can read and arrange, but I can’t write. If I get an idea I put it on tape and somebody else writes it out.

HP: Now, most soulful musicians don’t have that technical knowledge. Did that knowledge change the way you might have played before?

Nina: No. There was no conscious thought of that knowledge. When I studied for all those years, it was to be a concert pianist. Now that has nothing to do with the music of my people. It’s two separate things. But, I realize the advantages I have in composing and taking blues one step farther. Theory and harmony broadened my mind in music. I know what music is made of. The Beatles are doing it with their thing. If I want to take a particular form of blues somewhere else I have the equipment to do it But I never even thought of it.

HP: Your classical training didn’t make you look down your nose at funk?

Nina: Are you kidding? Me? As colored as I am? Shoot, I couldn’t wait to get back home, and do some dancing. You don’t know. What my people have is much more relaxing. (laughter)

HP: Why do you think some musicians can really get into funky music and others can’t even play a funky chord?

Nina: It’s very simple. Funk, gospel, blues is all out of slavery times, out of depression, out of sorrow. It’s logical that people from bad times will reflect their feelings in their communication. Music is part of the communication. If you lived it, you can do it. It’s even talking be-bop words. Now you noticed that I have a cultured manner of speaking. Tomorrow, I might be in a different mood and you wouldn’t recognize my voice. My people have very subtle slang, inflections and ways of saying things that has little to do with words. If you’re from the same place, you’ll feel the jargon and know exactly what’s happening. Same with any neighborhood cat. What he sees and hears and feels and lives makes him what he is. That’s what blues is. I believe in racial memory too. I’m sure I’ve got ancient African blood in me that has something to do with what I am.

HP: Do you ever feel some other blood in you? Maybe something white or something Spanish?

Nina: Sometimes, yes, when I think of reincarnation. Many times I feel different like a different person.

HP: Do you fed a strong closeness to any music other than Negro music?

Nina: I love all music. I mean that. But, I can’t stand loud guitars that make me deaf. Music is the center of my life. I love to travel to hear different kinds of music.

HP: Would you ever do an album of classical music?

Nina: Perhaps. I don’t think I can play it anymore. I’m going to do a concert of my own music with a symphony orchestra but that’s probably the closest I’ll ever get to it. I love the classics but there are many new ideas to be made into reality. I’d rather be concerned with my own thing. There are many masters of classical piano so I’ll leave it to them.

HP: Who are your main influences on keyboard?

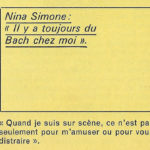

Nina: Oh many. Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, Horace Silver and even John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. They don’t play piano but their music feels the same to me. I’m also a nut for Bach as a composer. I’d say those are my major influences. I love the sound of the harpsichord too, especially Wanda Landowski when she plays Bach.

HP: Very often your music is filled with melancholy but the feel of the music, I guess the chords, aren’t funky sad. It’s like Jacques Brel. Sad but not funky sad. Do you think you play chords that way because of your classical training?

Nina: Now wait. That’s loaded. You’re talking about ME. I don’t want to analyze myself that close. I have no idea. It would be ridiculous to try. That’s like saying what might have been if some change in plans happened. But, I’ll tell you, my friend, last night I was alone and I was thinking what would I be now if I had been born in some other place, if I had lived a different life. Who could possibly know that? What, for instance, would I be now if I were raised in a non-racist society. But I’m sure many people wonder about these things.

Footage of Nina’s performance and behind-the-scenes interviews were included on the DVD Great Performances: College Concerts and Interviews.