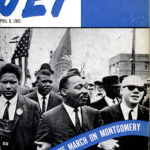

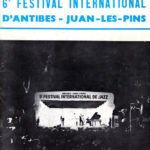

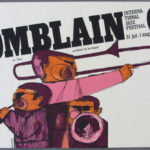

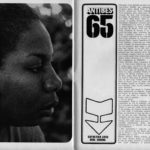

1965

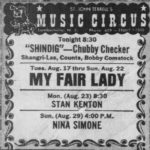

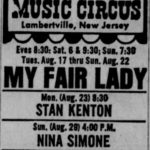

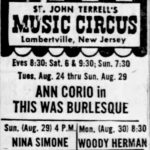

click each to enlarge

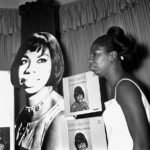

Lorraine Hansberry, friend and mentor of Nina Simone, died on January 12, 1965. Ms. Hansberry was a playwright and writer. She was the first African-American female author to have a play performed on Broadway. Her best known work, the play A Raisin in the Sun, highlights the lives of Black Americans living under racial segregation in Chicago. Following her death, Nina took one of Ms. Hansberry’s unfinished works and turned it into her song, To Be Young, Gifted, and Black.

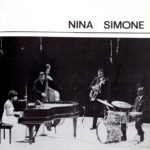

Nina performs at Lorraine Hansberry’s funeral:

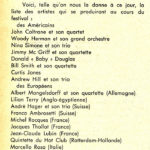

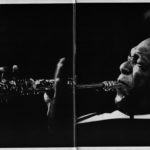

Nina Simone

She’s got a right to sing the blues – by Rolf Ehrenhardt

Blues singing is the cruelest of the arts. A man or a woman can be wealthy and/or contented and write a great novel, paint a masterpiece, pen a symphony for the ages. But blues singing is born in a swampland of misery and despair, nurtured on trouble and watered with tears. There is no record of anyone listed in the Social Register singing “I Loves You, Porgy” and making it sound like anything but an invitation to the waltz or an overture to a let’s-trade-wives session at Palm Beach.

Blues singing—good blues singing—comes from the gut and goes to the gut. Listen to Bessie Smith doing “Empty Bed Blues,” and it’s enough to tear your heart out. The oldest record I own is a 78 on the Perfect table. Cliff Edwards (maybe you remember him as Ukulele Ike) sings “It Had To Be You.” The record is worn, scratchy, and wobbles on the turntable. But enough of the song comes over to make me want to climb walls. I’m glad it’s an old record and scratchy. If it was new, and I could hear it clearly, I’d probably be injecting Sen-Sen directly into my veins.

That’s what blues singing does to me — to me and a lot of people like me who find something in this music we can’t find anywhere else. We know that the education of any good blues singer has to include disappointments without counting and grief without end. That’s too bad, but that’s the way it’s got to be. When you see a good bullfight — a duel that touches a primitive part of you that’s probably never been touched before — the bull dies. When you hear a good blues singer, a much being dies — a little.

I like most of Bessie Smith and all of Billie Holiday. I can listen to some of Ella Fitzgerald and most of those sad, wispy turns Helen Morgan recorded. I can remember being so drunk I was sober and listening to Tommy Lyman (whatever happened to him?) singing “I’ll Be Seeing You” and thinking that life couldn’t hold much more for me than that. Oh sure, some of Sinatra goes down easy. Some of Judy Garland. But up to about five years ago I had almost given hope that a good new blues singer would ever come along.

Then I heard Nina Simone sing “I Loves You, Porgy.”

Understand that good blues singing isn’t just a matter of voice training and phrasing. It’s the quality of the voice that counts — and the amount and kind of living the owner of the voice has known. It seemed to me Nina Simone’s voice had a quality that reminded me of a young Billie Holiday. Not Billie after the whiskey and heroin and the cops and the outrages had done things to her that should never be done to any human—but Billie in one of her quiet, more reflective blue moods, singing something like “Good morning, Heartache” and putting into it all the say yearning, the meanness of life, and the hope for something better that you’d expect from someone who’s been everywhere and done everything but is still young enough to dream that tomorrow will be different.

I listened to Simone singing “I Loves You, Porgy” and thought she might, she just might prove to be the greatest of them all. It was obvious she knew music, and I wasn’t surprised to learn she was an accomplished pianist. She was young at the time —about 21— and all her faults were young faults. With luck she’d grow out of them. With luck she’d live through all the insults to human dignity and the sly corrosion of the spirit any colored performer must suffer in America today—I don’t care how much money they make.

A little background music, professor…

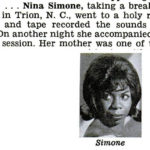

Nina Simone was born Eunice Waymon in Tryon, NC. She was one of eight children, and the family was poor. Picture a poor colored family of eight children in Tryon, NC (population: 1,985), and you’ll begin to dig how blues are born.

Nina’s father was a handyman and her mother was a housekeeper during the day and conducted services at the local church in the evenings. By the time she was eleven, Nina was playing piano and organ in her mother’s church, and singing in the choir. Later, she and two of her sisters formed a singing group and performed in church and at outside functions.

With the help of a benefactor, Nina was able to take classical lessons, and, eventually, study for a year at Juilliard in New York. Meanwhile her family moved to Philadelphia, and Nina joined them there, making money by giving piano lessons and accompanying voice students. She found she had a flair for improvising, both in her singing and on the piano. In the summer of 1954 she took a job as a singer in a small club in Atlantic City. She changed her name then, from Eunice Waymon to Nina Simone, to keep her new career from her piano students and from her parents.

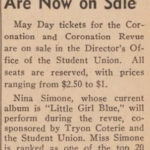

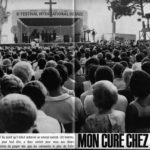

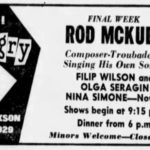

Engagements in clubs around Philadelphia led to an appearance with her own trio at the New Hope Playhouse Inn, Bucks County, PA. She made “I Loves You, Porgy” and saw it hit the best-seller charts. Her first album was “Little Girl Blue.” After that came New York’s Village Gate, Town Hall, Carnegie Hall, top clubs in Chicago, Detroit, Washington, jazz festivals at Philadelphia and Newport. She’s been on TV shows and in nightclubs and has played concerts across the country. She’s got a flock of albums with her name on them and, for a blues singer, everything appears to be coming up roses. That’s the way it appears.

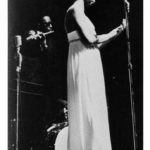

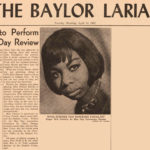

She’s a big woman, not petite, and she’s handsome rather than beautiful. But it’’s not the kind of face you’ll forget in a hurry, and time seems to be refining it, cutting it down to its essential bone structure. The eyes are big and luminous. There is something at once ungainly and touching about her figure. She has a stage presence. She has a kind of withdrawn dignity. She’s a lot of woman and a lot of singer.

All the foregoing — form the time we said “A little background music, professor” — is fact, more or less. What follow is opinion.

There are a lot of things that can do a young singer in. She can become infatuated with her own importance until the day when one of the short, fat, cigar-chewing men who control music in this country proves to her that she was no importance at all. Or the young singer can get hung up — on one or more of many things: dope, booze, love for the wrong man. Or the young singer can succumb to the temptations of the world of nightclubs and one-night stands and concerts in strange cities and hotel living and a lot of fast money and a lot of offers from men to help her career. And some of the really can.

The young singer can resist all these things, or withstand them, and still not fulfill her potential. She can wear out her voice with too many hours in smoke-filled cellar clubs. She can listen to false friends and waste her time with a hundred worthless “causes” or a hundred phony charities. Or she can make mistakes in the selection of the songs she sings and the direction in which her career is going.

It is this last pitfall I hope most urgently that Nina Simone can avoid. The most recent album of hers I’ve heard (“Nina Simone in Concert” on the Philips label) includes several things that were better left unsung — at least by this potentially great blues singer. “Pirate Jenny” is from “The Three-Penny Opera” and belongs to another country, another age. “Old Jim Crow” has a message all right, but not for the people who listen to Nina Simone. “Mississippi Goddam” is an embarrassingly breezy tune for the subject it treats.

What I’m trying to say is that here is a voice and a talent made for blues singing. It is too personal for songs of protest and too good for folk songs. It is, in my opinion, not even a voice for the concert hall. It belongs in small clubs. It is an intimate voice, and it should be used in the small hours and not for big parades.

That’s why I hate to hear Nina Simone sing anything but the good blues numbers — the old and the new. When I think of what she might do with some of the Billie Holiday things, an icy hand goes around my heart. When I think of how she could update some o the early Bessie Smith, I’m ready to roll over and play dead.

Because I think this woman has the vocal equipment to be one of the greatest, and it hurts me to hear her do all those nice, folksy things and those songs of protest. What the hell good is a song of protest? There hasn’t been a good one done since Billie Holiday did “Strange Fruit,” and do you suppose even that changed anyone’s mind or made a saint out of a sinner?

When I say Nina Simone “has got the right to sing the blues,” I don’t mean her life has been one long series of miseries and misfortunes — although I doubt if she’s a stranger to sadness. What I mean is that she has the right, the privilege, to sing some of the greatest songs this country has produced. She has the voice for it. She has the musical training for it. And it will be nothing less than a tragedy if she spends her vocal wealth on brassy folk songs and tunes that turn green before they’re worn a month.

I asked a musician friend of mine — a somewhat enigmatic drummer whose opinions I respect — what he thought of Nina Simone. He stared overhead a long moment. Finally, “She’s got the show,” he said, “but, has she got the go?”

He meant — or I think he meant — what I’ve been trying to say: she’s got the right to sing the blues. It’s the cruelest of the arts, but in this mean, imperfect world an artist should do what he does best. The blues grow out of the suffering and the degradation and the shattered dreams of the singer.

But they make the listener more human.

And in this day and age, anyone who can make people feel more human has an obligation to do it. God knows we need it.