1963

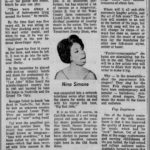

One convention places the singer somewhere between the actor and the musician, both of whose disciplines the vocalist draws on to shape his or her art. It has been my experience that most popular singers who have some knowledge of their craft — and “jazz singers,” if there be such creatures, fall into this category — tend to concentrate on one at the expense of the other, with the result that the expressive potential to be gained from the fusion of two arts is seldom achieved. In fact, it would seem that the exaggeration of one of the two elements makes for a product that is, more often than not, dilute and mannered.

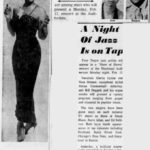

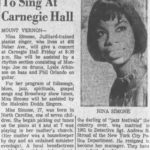

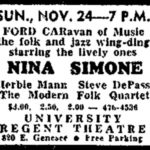

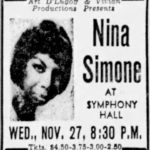

Miss Simone, however, has fused both disciplines into one of the most affecting and finely wrought of current vocal styles. She is one of today’s consummate popular singers (I leave the discussion of her merits as a “jazz singer” to others; I’d rather just listen to the singer, thank you), with an approach that is both musically arresting and emotionally gratifying.

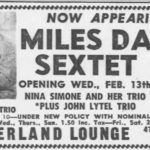

She speaks directly from the heart. And that is her great success, for her whole approach is aimed at evoking an immediate emotional response in her listeners. More often than not she succeeds, as she demonstrated at her Sutherland engagement. She had the crowd with her all the way on the uptempo pieces; yet her quiet, more intimate numbers brought an attentive, rapt silence over the audience. Everyone was listening; everyone was sharing.

From the start, her musicianship has been flawless (she initially began her career as a pianist and only later she started singing). As an instrumentalist she has technique and power to spare, yet rarely engages in virtuoso display. Rather, her accompaniments and improvisations are already guided by artistic sensibility, impeccable taste, and an awareness of the total musical entity. Her usually spare accompaniments enhance, underline, and bring out the vocal line, and the solos advance the mood and climate of the song, leading inevitably back into the vocal line.

One of the finest illustrations of her ability to build and sustain a mood was the dulcet Schubert-like piano solo “Where Is Your Heart?”, a very moving, flowing, and economical piece that was striking in its unabashed but uncloying romanticism. At the end of her exposition of this, Miss Simone segued naturally into a vocal “If You Knew,” which continued the mood of wistful longing of the instrumental selection, demonstrating her ability to penetrate to the emotional essence of her material. It was an ardent, luminous performance, for so perfectly did the two selections flow into one another that they might be considered one.

She brought to life Oscar Brown Jr.’s “Rags and Old Iron” and his setting of “Work Song”; I found her projections of these two pieces much more convincing and far less coy than the composer’s often embarrassingly over-cute and self-conscious renditions. Miss Simone avoided this pitfall by understating them. An Israeli folk song was the only up-tempo offering of the set and generated quite a bit of heat. A medley of her best-selling recordings was perhaps the least effective of her selections, for it was pitched a bit too low for comfortable singing on all the numbers, and truncated versions teased rather than satisfied.

Perhaps it was a result of the sound system, but I found the quintet’s ensemble playing a bit muddy and cluttered much of the time. Other than that, I carried away no real impression of the group per se.

Vibraharpist Lytle’s trio is an attractive, unpretentious group that is almost entirely built around his playing. For the most part, organist Harris stays in the background, providing an unobtrusive harmonic carpet for the vibist to dance upon.

Unfortunately, he dances a bit too long and not always lightly. Lytle’s style has a couple of weak spots, I feel. He has a tendency to overdecorate, to try to play too many notes, which imparts a cold, mechanical quality to his playing at times (and this was especially noticeable on the languid balled “Willow, Weep For Me” and on “I’ll Remember April”, the ending of which was pointlessly stretched out ad infinitum). On “The Way You Look Tonight”, taken at a plodding tempo, Lytle played fleetly but again too automatically. After a while it became tedious.

Drummer Hinnant acts merely as timekeeper; in a group this small, it would seem he could participate more intimately.